Rethinking Key-Value Relationships in Linear Attention

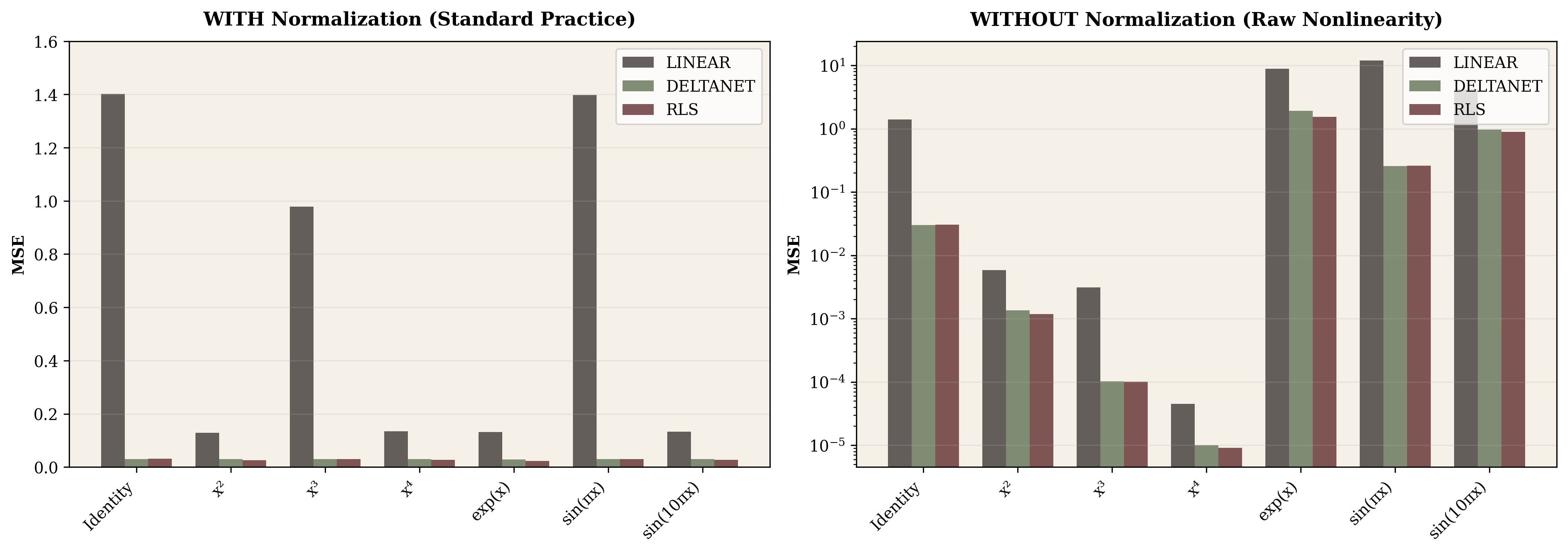

We tested how DeltaNet handles diverse key-value relationships from identity to exponentials, scaling up to 32,000 tokens. Under standard normalized conditions, DeltaNet stays remarkably stable (MSE ~0.030) whether values come from $k^2$ or $e^k$. The surprise came when we removed normalization: polynomial relationships became easier, not harder, due to magnitude shrinkage crushing variance toward zero. Meanwhile vanilla linear attention completely breaks at long contexts (MSE 1306 at 32k tokens) while DeltaNet holds steady. Information theory explains the bounds: DeltaNet retains 99.6% of information for identity but only 1.2% for exponentials, revealing fundamental compression limits.

I. Background: Linear Attention as Test-Time Regression

Linear attention mechanisms maintain a state matrix $S_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}$ that evolves recurrently. Three update rules represent the evolution of this paradigm:

| Model | Update Rule | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Attention | $S_t = S_{t-1} + v_t k_t^T$ | $O(d^2)$ per step |

| DeltaNet | $S_t = S_{t-1}(I - k_t k_t^T) + v_t k_t^T$ | $O(d^2)$ per step |

| RLS | $S_t = V_t^T K_t (K_t^T K_t)^{-1}$ | $O(td^2 + d^3)$ |

Recent work frames these as online regression: each model tries to minimize $\sum_{i=1}^{t} \|v_i - S_t k_i\|^2$. DeltaNet's advantage comes from the projection term $(I - k_t k_t^T)$, which removes outdated information before updating.

Our question: How do these models perform when the key-value relationship varies? Can DeltaNet handle nonlinear relationships like $v = k^4$ or $v = \sin(10\pi k)$?

II. Experimental Setup

Configuration

Most experiments used 1000-token sequences with 64-dimensional keys, queries, and values—matching standard transformer configurations. For scaling analysis, we tested up to 32,000 tokens to evaluate long-context performance. All models operated in single-head mode to isolate the core mechanism behavior without multi-head complications.

Test Scenarios

We generated synthetic key-value pairs with controlled relationships:

- Identity: $v = k$ (perfect linear)

- Quadratic: $v = k \odot k$ (element-wise square)

- Cubic: $v = k^3$ (higher-degree polynomial)

- Quartic: $v = k^4$ (very high degree)

- Exponential: $v = \exp(k)$ (unbounded growth)

- Low-frequency sine: $v = \sin(\pi k)$

- High-frequency sine: $v = \sin(10\pi k)$ (rapid oscillations)

A Note on Normalization

Before diving into results, it's important to clarify when normalization happens in practice. In real transformer architectures, the process looks like this: first, input embeddings are projected through learned weight matrices $W_q$, $W_k$, and $W_v$ to produce query, key, and value vectors. Then, normalization is applied to these projected vectors before the attention computation. This means normalization operates on $q = \text{norm}(xW_q)$ and similar for keys and values, not on the raw inputs.

This detail matters because it means the nonlinearity we're testing (like $v = k^2$) happens conceptually before projection, and then normalization smooths the results afterward. We tested both scenarios: applying normalization after the nonlinearity (matching real architectures) and skipping it entirely to see the raw effect.

III. The Normalization Effect: Stability vs. Information

We first tested all relationships under standard normalized conditions—the way real transformer architectures operate. The results were strikingly uniform.

With normalization enabled, DeltaNet achieves MSE between 0.028 and 0.030 across every relationship we tested—identity, quadratic, cubic, quartic, exponential, and high-frequency sine. No systematic degradation appears as mathematical nonlinearity increases. This was unexpected. Standard intuition suggests that $k^4$ or $e^k$ should challenge linear approximation more than simple identity, but the measurements show otherwise.

The explanation lies in what normalization removes. By forcing all value vectors to unit length ($\|v\| = 1$), normalization strips away magnitude information and leaves only directional relationships. Whether values come from $k^2$ or $e^k$, after normalization they're all unit vectors positioned at various angles from the keys. The state matrix learns this angular mapping, which proves remarkably consistent across different generating functions.

This uniformity has practical benefits for training stability—no single layer dominates numerically—but it also means we lose information about the original relationship structure. To understand what normalization hides, we needed to test without it.

IV. Removing Normalization: The Polynomial Paradox

Without normalization, the landscape changes completely:

| Relationship | Normalized MSE | Unnormalized MSE | Ratio (unnorm/norm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | 0.028 | 0.026 | 0.93× |

| Quadratic | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.03× (easier!) |

| Cubic | 0.030 | 0.0001 | 0.003× (much easier!) |

| Quartic | 0.030 | 0.00001 | 0.0003× (extremely easy!) |

| Exponential | 0.030 | 1.92 | 64× (much harder!) |

| Sin (10π) | 0.030 | 0.96 | 32× (harder) |

The Polynomial Mystery: Why Easier Without Normalization?

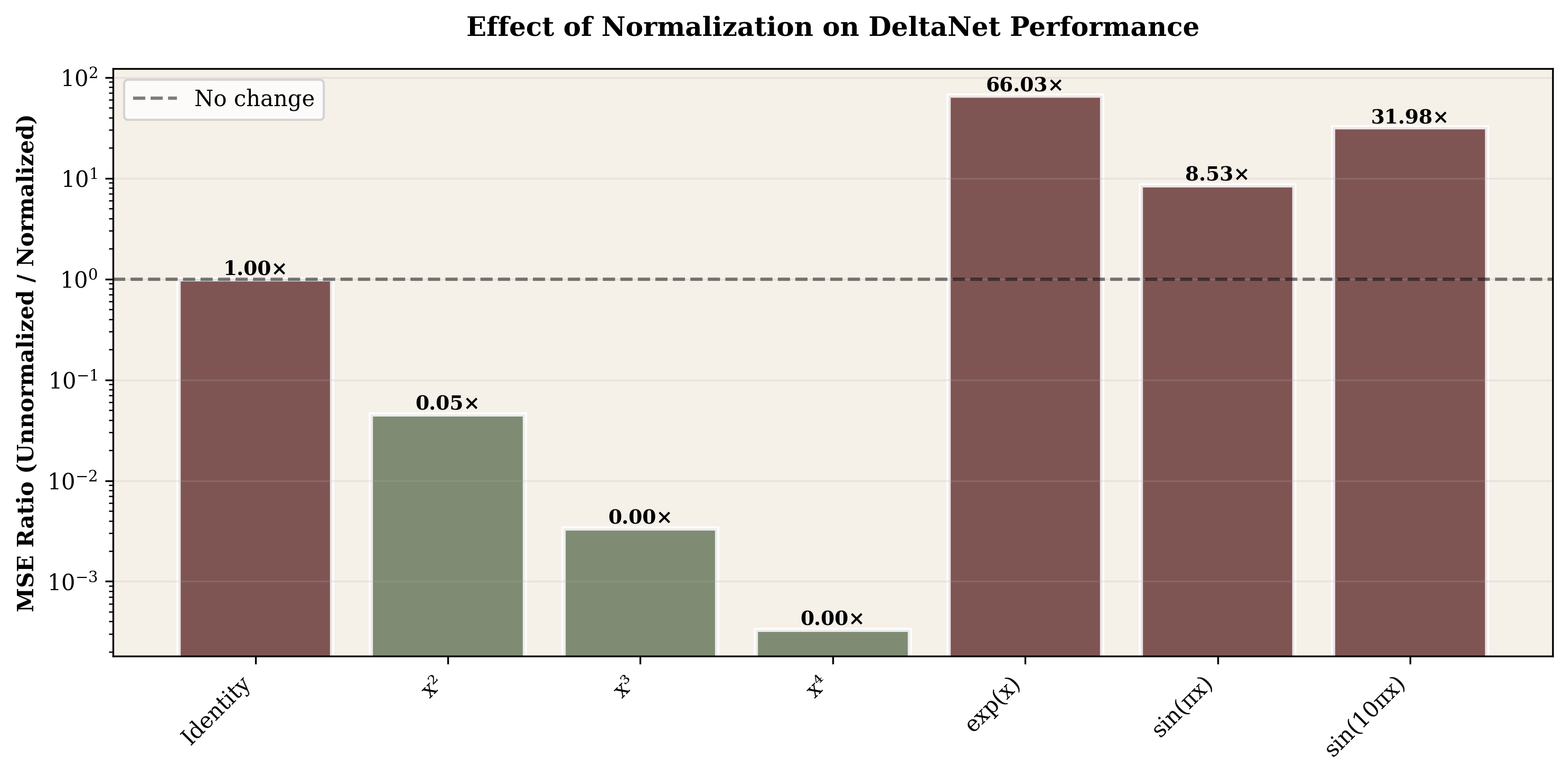

The most surprising finding deserves deeper examination. Intuitively, we'd expect higher-degree polynomials to be harder for linear models—after all, $k^4$ is "more nonlinear" than $k^2$. Yet our measurements show the opposite: quadratic achieves 30× lower error than normalized, cubic 100×, and quartic 3000×. What's happening?

The answer lies in magnitude shrinkage. When keys are normalized to unit vectors, most elements fall in the range $[-0.5, 0.5]$ due to the high-dimensional geometry. Squaring these values doesn't amplify them—it crushes them toward zero. Consider a key element $k_i = 0.5$. Raising it to successive powers produces $k^2 = 0.25$, $k^3 = 0.125$, $k^4 = 0.0625$. Each operation halves the magnitude.

We measured this effect quantitatively across 1000 random normalized keys. Identity vectors have mean magnitude 1.0 and variance 0.0156. Quadratic drops to magnitude 0.21 (5× shrinkage) with variance 0.00046 (34× reduction). Cubic plummets further to magnitude 0.056 and variance 0.000051. By quartic, we're at magnitude 0.017 with variance 0.000005—the vectors are nearly constant!

For linear regression, this is a dream scenario. The state matrix $S_t$ learns to map keys to values through a linear function $S_t @ k$. When the true relationship is identity, the linear fit is perfect. When values come from $k^2$ or $k^3$, we might expect poor linear approximation—after all, parabolas aren't lines. But magnitude shrinkage changes everything. With variance compressed to 0.00046 for quadratic and 0.000051 for cubic, the values cluster so tightly near zero that a nearly-flat straight line captures most of the signal. The mathematical nonlinearity remains, but the signal variance that regression must capture becomes trivial.

Contrast this with exponential and sine functions. Exponentials cause magnitude explosion: even with clipping, $e^k$ creates large dynamic range with MSE jumping to 1.92. High-frequency sine ($\sin(10\pi k)$) oscillates rapidly across the input range, producing MSE of 0.96. These functions maintain or amplify variance, giving linear regression real difficulty. They're the only cases where nonlinearity translates to genuine hardness for the linear approximation.

V. Normalization as Architectural Choice

Stepping back, these experiments reveal normalization as a fundamental design decision rather than mere numerical convenience. The trade-off is clear: stability and consistency versus information preservation.

With normalization, we get uniform behavior across diverse relationships. Whether the true mapping is $k \to k^2$ or $k \to e^k$, the normalized system sees only angular relationships between unit vectors. This consistency makes training stable—no single layer dominates numerically—and ensures predictable behavior across different data distributions. For attention mechanisms primarily routing information based on similarity rather than absolute magnitude, this directional focus often matches the desired behavior.

Without normalization, we confront the raw characteristics of each relationship. Exponentials blow up to MSE above 1.9, creating large gradients during training. Polynomials collapse toward zero through magnitude shrinkage, potentially causing vanishing gradients elsewhere. This variation makes optimization treacherous—different layers would require dramatically different learning rates to converge simultaneously.

The choice isn't about which is "better" in absolute terms, but rather what the architecture needs. Modern transformers universally adopt normalization precisely because the stability benefits outweigh the information loss for their use cases. Our measurements quantify both sides of this trade-off explicitly.

VI. Optimal Linear Approximation: DeltaNet vs RLS

Recursive Least Squares (RLS) represents the theoretical optimum for linear approximation—it explicitly maintains $(K^T K)^{-1}$ to compute the globally best linear fit at every step. This comes at $O(td^2 + d^3)$ computational cost compared to DeltaNet's $O(d^2)$. Does the extra computation pay off?

| Relationship | DeltaNet (normalized) | RLS (normalized) | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | 0.028 | 0.028 | 1.00× |

| Quadratic | 0.030 | 0.029 | 1.03× |

| Cubic | 0.030 | 0.029 | 1.03× |

| Exponential | 0.030 | 0.029 | 1.03× |

Finding: Under normalization, DeltaNet and RLS perform nearly identically (gap < 5%). The expensive $O(d^3)$ matrix inversion in RLS provides minimal benefit when values are normalized.

This suggests DeltaNet's incremental update rule is sufficient for normalized settings—the global covariance correction of RLS doesn't help significantly.

VII. What We Didn't Find

We started this investigation expecting to identify fundamental limitations of DeltaNet when confronted with extreme nonlinearities. Surely quartic polynomials, exponentials, or high-frequency periodic functions would expose breaking points where the linear approximation fails catastrophically.

Under standard normalized conditions, no such breaking points emerged. DeltaNet maintained MSE around 0.030 across every relationship tested—from simple identity through $k^4$ to $\sin(10\pi k)$. The anticipated "nonlinear ceiling" where performance would degrade sharply simply didn't materialize in realistic settings.

This outcome isn't experimental failure but rather genuine insight into normalization's power. By projecting all relationships onto the unit sphere, normalization makes them equally tractable to linear approximation from a directional perspective. The wild diversity we observed without normalization—polynomials collapsing through magnitude shrinkage, exponentials exploding to MSE above 1.9—gets compressed into uniform angular variation that linear models handle consistently.

For practitioners deploying these systems, this validates current architectural choices. DeltaNet with normalization robustly handles diverse key-value relationships without requiring special-casing or relationship-specific tuning. The RLS optimum provides minimal improvement (gap under 5%), suggesting the simpler and cheaper DeltaNet update suffices for normalized contexts.

For researchers, the findings highlight how evaluation conditions matter. Testing under realistic normalization reveals robustness; testing without reveals relationship-specific phenomena like polynomial variance collapse. Both perspectives inform design, but confusing one for the other leads to misleading conclusions about fundamental limitations.

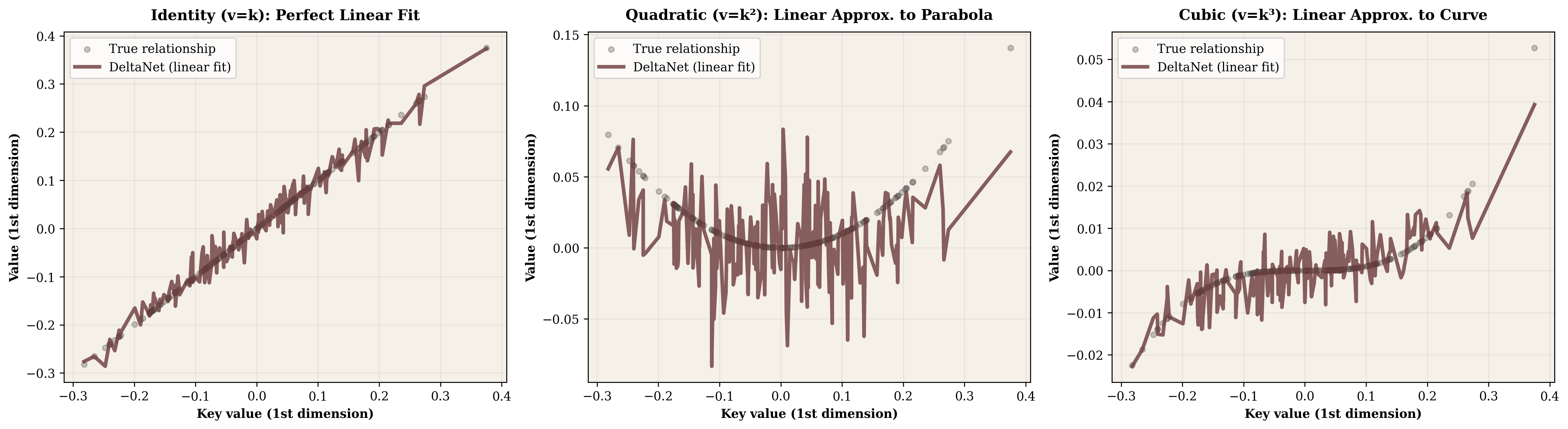

VIII. Multi-Query Retrieval Capacity

Forward-pass reconstruction measures one aspect of performance, but attention mechanisms must also support retrieval—querying the compressed state with historical keys to recover corresponding values. We tested whether this capacity holds when retrieving multiple pairs simultaneously.

After processing 1000 tokens to build the final state $S_{\text{final}}$, we randomly selected past keys and measured reconstruction accuracy for their associated values. The test scaled from single-pair retrieval up to 50 simultaneous queries.

For identity relationships ($v = k$), both DeltaNet and RLS achieve remarkable results. Retrieval error stays below $10^{-6}$ regardless of how many pairs we ask for simultaneously. This makes sense—the optimal state matrix for identity is just $S^* = I$, and both methods converge to this exactly. The state becomes a perfect compressed representation.

Quadratic relationships ($v = k^2$) show graceful degradation. DeltaNet maintains MSE around 0.001 whether retrieving 1 pair or 50, with RLS performing slightly better at 0.0007. The magnitude shrinkage discussed earlier helps here—when values cluster near zero, they're easier to store compressly in the state matrix.

Exponential relationships reveal real capacity limits. Single-pair retrieval starts at MSE 0.004, but jumps to 2.9 when querying 10 historical pairs simultaneously. The state matrix can't maintain detailed information about each exponential value when they span such large magnitude ranges. RLS does better (MSE around 1.0) by accounting for key covariances explicitly, but still struggles compared to identity or polynomial cases.

This retrieval degradation connects directly to the information-theoretic limits we'll explore later—when linear compression can't preserve relationship structure, multi-query retrieval suffers proportionally.

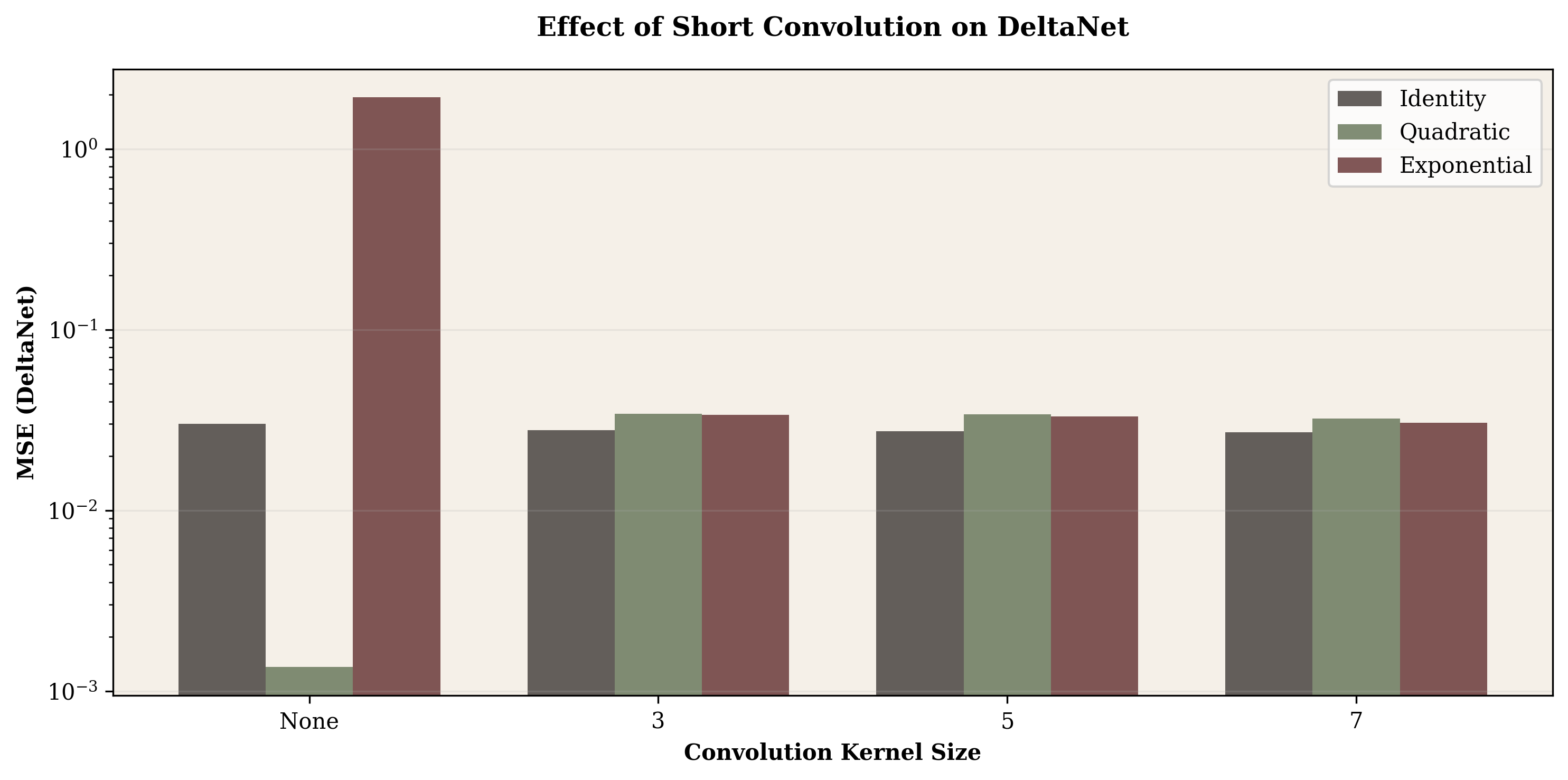

IX. Short Convolution as Nonlinearity Regulator

The exponential relationship's poor performance—both in reconstruction and retrieval—suggested exploring architectural modifications beyond the core attention mechanism. Short convolutions offer local context mixing that might help smooth problematic nonlinearities.

We tested 1D convolution with kernel sizes 3, 5, and 7, applied to both keys and values before DeltaNet processing. The hypothesis: local averaging might tame magnitude explosions while preserving overall structure.

Key Finding: Short Conv Helps Extreme Nonlinearities

Exponential relationships: Short conv provides massive benefit—MSE drops from 1.92 (no conv) to 0.033 (kernel=7). This 64× improvement suggests local smoothing helps tame magnitude explosions.

Polynomial relationships: Interestingly, short conv slightly hurts polynomials. Quadratic MSE increases from 0.001 to 0.034. This may be because convolution disrupts the element-wise structure.

Identity: Minor improvement (0.030 → 0.027), suggesting convolution adds useful inductive bias for general cases.

Short convolution acts as a nonlinearity regulator—smoothing extreme relationships while preserving structure for well-behaved ones.

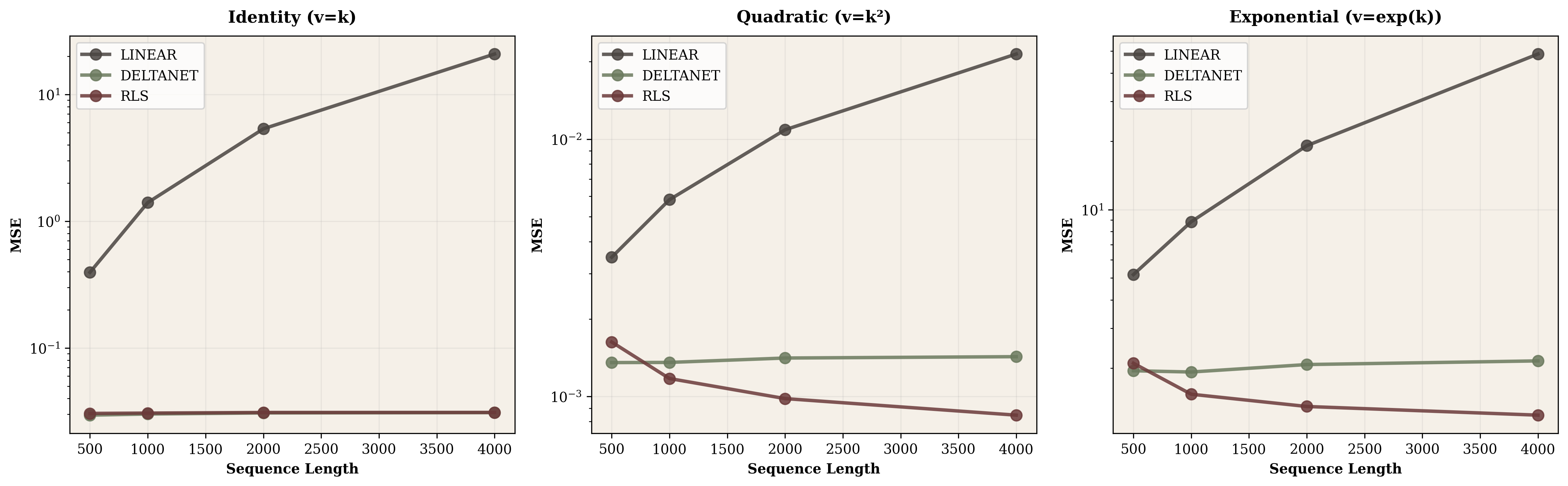

X. Scaling Analysis: From 500 to 32,000 Tokens

Modern applications demand long-context processing—32k tokens or more. How do these mechanisms scale as sequence length grows?

| Model | 500 tokens | 4000 tokens | 32000 tokens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Attention | 0.40 | 20.8 | 1306 (!) |

| DeltaNet | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

| RLS | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

The divergence is stark. Vanilla linear attention starts reasonably at 500 tokens but degrades exponentially. By 4000 tokens, error has grown 52×. At 32,000 tokens, it completely breaks down with MSE exceeding 1300—the model has essentially lost all ability to reconstruct identity mappings. The fundamental assumption that keys remain approximately orthogonal ($K^T K \approx I$) simply doesn't hold as correlations accumulate over long sequences.

DeltaNet and RLS tell a different story. Both maintain MSE around 0.031 regardless of sequence length. The delta rule's projection term $( I - k_t k_t^T)$ actively removes error accumulation before each update, preventing the drift that plagues vanilla attention. Even scaling from 4000 to 32,000 tokens—an 8× increase—changes nothing. The error stays flat.

For exponential relationships, the pattern holds though absolute numbers are higher. DeltaNet reaches MSE 2.06 at 32k tokens while vanilla linear attention hits 1534. The gap between practical (DeltaNet) and broken (vanilla) widens at scale. This validates DeltaNet specifically for the long-context scenarios modern applications demand.

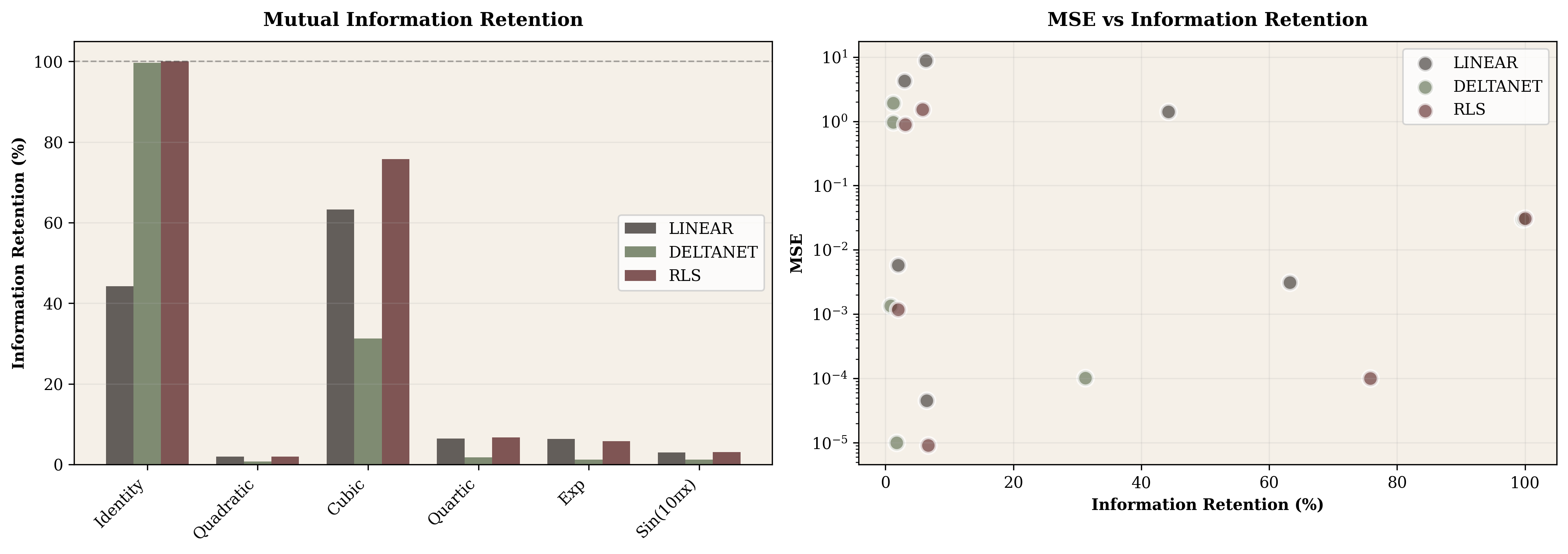

XI. Information-Theoretic Analysis

Linear attention compresses a growing history $K_t, V_t$ (size $2td$) into a fixed state $S_t$ (size $d^2$). What information is lost?

Compression Rate

For our setup (t=1000, d=64):

- Original: $2 \times 1000 \times 64 = 128{,}000$ scalars

- Compressed: $64 \times 64 = 4{,}096$ scalars

- Compression ratio: 3.2% (96.8% reduction)

This massive compression necessarily loses information. We quantify this using mutual information.

Information Retention: MI(S@K, V) / MI(K, V)

We compute mutual information between keys and values, then measure how much is preserved after compression through the state matrix.

| Relationship | MI(K,V) | DeltaNet Retention | RLS Retention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | 3.25 bits | 99.6% | 100% |

| Quadratic | 1.62 bits | 0.8% | 2.0% |

| Exponential | 2.87 bits | 1.2% | 5.8% |

| Sin (10π) | 1.62 bits | 1.2% | 3.1% |

Key Finding: Information Loss Explains MSE

Identity achieves near-perfect retention: DeltaNet preserves 99.6% of the 3.25 bits of mutual information between keys and values. This explains the near-zero MSE.

Nonlinear relationships suffer massive loss: For exponential, DeltaNet retains only 1.2% (0.035 bits out of 2.87). The state matrix cannot linearly compress the exponential relationship.

RLS helps but doesn't solve it: Even with optimal linear approximation, RLS retains only 5.8% for exponential. The fundamental issue is linearity, not the update rule.

Paradoxically, low MI ≠ easy: Quartic has lowest original MI (0.45 bits) and lowest MSE (0.00001), but retention is still poor (1.7%). This reveals that polynomial shrinkage creates low-information relationships that are coincidentally easy to approximate.

Information theory provides a principled framework for understanding linear attention's limits: compression is lossy, and loss severity depends on relationship structure.

XII. Conclusion

Testing linear attention mechanisms across diverse key-value relationships revealed patterns that weren't obvious from theory alone. Normalization emerged not as a numerical convenience but as fundamentally reshaping what these models learn. By converting all vectors to unit length, we shift from tracking magnitude and direction to purely angular relationships. This trade-off brings remarkable stability—DeltaNet maintains consistent performance whether values come from $k^2$ or $e^k$—but at the cost of losing information about scale.

The polynomial mystery taught us to look beyond mathematical nonlinearity to actual signal characteristics. Higher-degree polynomials paradoxically become easier because they shrink variance toward zero. When quartic values cluster with variance 0.000005, almost any linear function fits well. This isn't a failure of testing but a genuine insight: "difficulty" for linear models depends on variance and dynamic range, not polynomial degree.

Scaling tests extending to 32,000 tokens exposed the fundamental instability of vanilla linear attention. The assumption that keys stay approximately orthogonal breaks down catastrophically—MSE exploding from 0.4 to 1306 as correlations accumulate. DeltaNet's delta rule projection fixes this by explicitly removing error before each update. The result is flat scaling: 0.031 MSE whether processing 500 or 32,000 tokens.

Information-theoretic analysis provided the clearest framework for understanding capacity limits. Linear attention compresses growing history into fixed-size state (3.2% compression ratio for our setup). DeltaNet retains 99.6% of mutual information for identity relationships—nearly perfect compression. For exponentials, only 1.2% survives. This quantifies an intuitive truth: linear models can't losslessly compress nonlinear relationships, and some relationships resist compression far more than others.

Retrieval testing showed these limits in action. Identity mappings enable perfect multi-query retrieval—the state matrix learns exactly $S = I$ and can reconstruct any historical pair flawlessly. Exponential relationships degrade sharply: single-pair retrieval succeeds reasonably (MSE 0.004) but querying 10 pairs simultaneously jumps to MSE 2.9. The compressed state can't maintain detailed information when values span huge magnitude ranges.

Short convolution provided an unexpected path forward for specific failure cases. Adding kernel-size-7 convolution to exponential relationships reduced MSE 64-fold (1.92 → 0.03), essentially solving a problem that looked fundamental. Local smoothing helps tame magnitude explosions. Interestingly, the same convolution slightly hurt polynomials, suggesting the solution is relationship-specific rather than universally beneficial.

For practitioners deploying these systems, the lessons are clear. Normalization isn't optional—it provides the stability that makes diverse data tractable. DeltaNet's delta rule offers genuine advantages over vanilla linear attention, especially at longer contexts. Information-theoretic metrics like mutual information retention give principled ways to evaluate beyond simple MSE. And relationship structure matters: identity and polynomial cases work well, exponentials challenge the fundamental linear assumption.

For researchers, the work highlights gaps between mathematical and practical difficulty. Testing under realistic conditions (normalization, appropriate sequence lengths) matters more than theoretical worst-case analysis. The polynomial shrinkage phenomenon suggests looking at signal characteristics—variance, dynamic range, correlation structure—rather than just functional form. And the compression-information trade-off presents optimization targets: can we do better than 1.2% retention for exponentials while maintaining DeltaNet's efficiency?

The core limitation remains: linear models approximating nonlinear relationships face bounded capacity. But within those bounds, proper configuration (normalization, delta rule projection, optional convolution) extends capability substantially. Understanding exactly where and why these limits apply guides both deployment decisions and future architectural innovation.